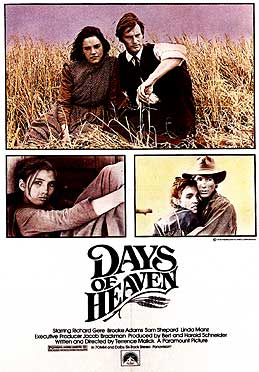

Probably the most enduring filmic image that has stayed with me from 2007 is this scene from Terrence Malick's sophomore film "Days of Heaven." Praise must go to Oscar-winning cinematographer Nestor Almendros who also worked on another favorite of mine François Truffaut's "Domicile conjugal" (aka Bed and Board).

For this special scene - a stunning sequence shot of locusts where the insects ascend to the sky, they dropped peanut shells from helicopters and had the actors walk backwards while running the film in reverse through the camera. When it was projected everything moved forward except the locusts! The result is nothing short of magical. It's a sequence I will remember for the rest of my life.

Almendros wrote in his now expensive and out of print book A Man With A Camera - "Since I lack imagination, I seek inspiration in nature, which offers me an infinite variety of forms." Speaking of working with Malick on Days he said "My job was to simplify the photography, to purify it of all the artificial effects of the recent past."

In the run up to shooting he and Malick studied the silent films of Griffith and Chaplin, aiming to capture the period of the film. They also attempted, and one may argue successfully, recreated the arid loneliness of American realist painter Andrew Wyeth's work and the warmth of painter Edward Hopper's interiors.

Almendros writes in his book "Nature's most beautiful light occurs at extreme moments, the very moments when filming seems impossible" and for Days of Heaven that moment of light was often the precious minutes between sunset and nightfall - a magical time zone when the almost dying light turns everything a burnished gold.

It's this death of light that is also spiritually reflective of the passage of the main character Bill played most affectively by Richard Gere in one of his strongest outings. The decisions he makes draw him ever deeper into a personal kind of hell and in many ways the locusts also represent this. So much of the emotional content in this film is conveyed visually without dialogue, the cinematography always servicing the story and lifting it.

The startling Criterion edition is just magical and I own quite a few of their discs but would most certainly pick this disc if you asked me to only keep one.

Almendros struggled with the union crew because they didn't understand what he was attempting to do. They wouldn't let the light be - he would have to go around the set turning off lights, he also had to fight with them to go against standard wisdom when he wanted to shoot actors from below against a white, burned out background. Almendros would not use any fill lights to accentuate the actors' faces. They are generally backlit and illuminated by source light bounced off the ground. He also used real firelight to illuminate faces and mirrors to enhance light inside the house.

He also shot much of the film using a unconventional Panaglide (a competitor to the Steadicam) so he could flow with the action and Malick. Additional he pushed the sensitivity of his negative to the max with this underexposure giving the film a painterly look. And he did all his special effects in camera.

In viewing "Days..." one should also consider the work of Haskell Wexler who due to Almendros's commitments elsewhere had to finish the film when it went over scheduled shooting time. The Criterion edition features a short interview with him in which he discusses in worshipful tones how he emulated Almendros.

No comments:

Post a Comment